While black elites are quite comfortable to be identified as merely black, and to quibble over what accent of English they speak with rather than whether they have preserved any semblance of their native heritage, many ordinary South Africans find the erasure of their identity in the upwardly mobile streams of cosmopolitan South Africa to be an alienating experience. Some young black people now speak little of their “native” tongue. The ANC under Ramaphosa has attempted to disempower traditional elites, to build towards a homogeneous black republicanism. The Bikoists, Pan-Africanists and Fallists at the university have whittled away the acceptance of languages other than English. People are encouraged to identify first with race, and then only secondarily with a tangible cultural heritage. This appears to be the current trend.

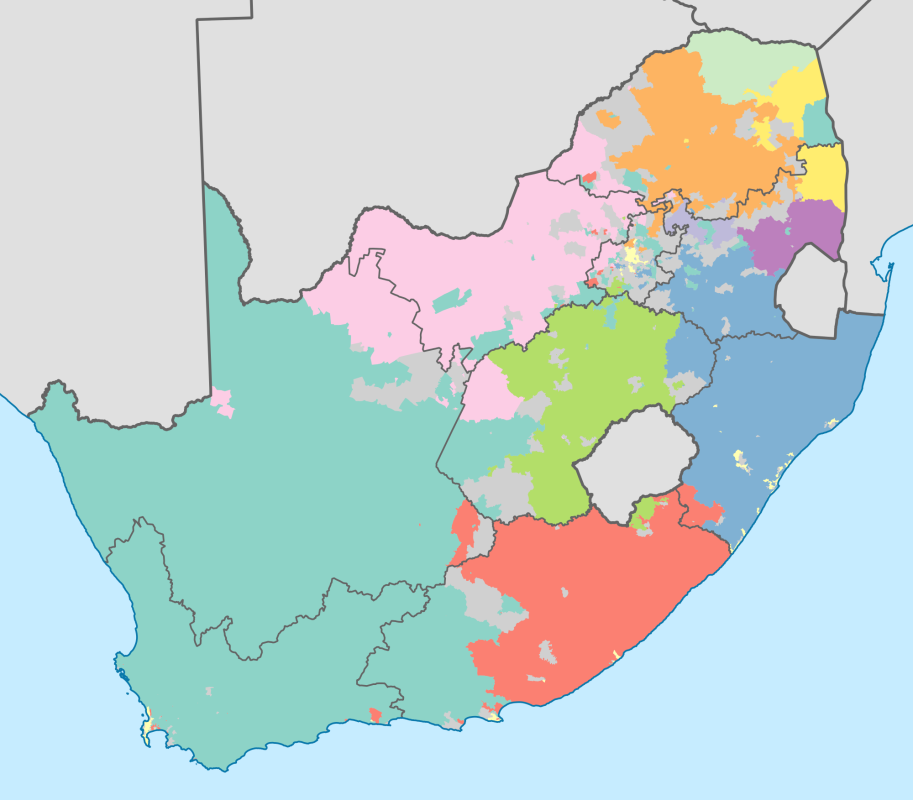

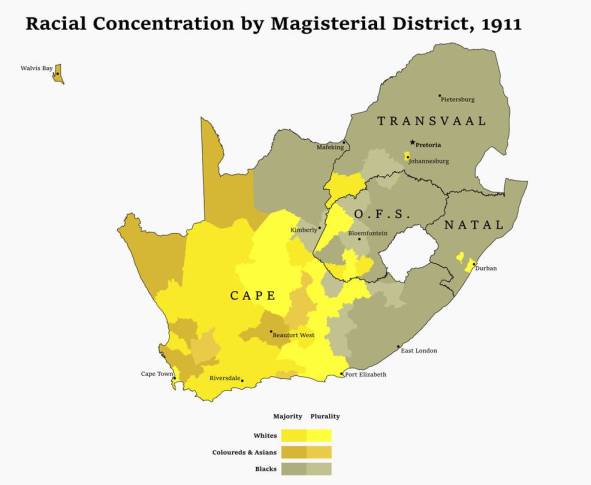

But in South Africa, much as in the rest of the world, identities of the past take a long time to die. The map below is from the 1911 census, but as a comparison with the 2011 maps beneath it demonstrates, the conquests by Bantu and European powers between 1300 and 1900 left an indelible mark that 100 years of population movement, both forced and organic, could not shift.

It should surprise nobody that the Zulu king has threatened secession, in defence of the traditional aristocratic hierarchy and the royal land possessions. But beyond the persistence of ethnic identity, something stranger is happening in South Africa. The idea of the Cape has persisted sufficiently to trigger four distinct independence movements, one Afrikaner-nationalist, one Khoe, one Cape-Coloured, and one cosmopolitan. What to make of these relatively marginal movements is hard to say, but in the wake of the emerging suppression of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction, and the increasing efforts to dispossess minorities of their place in the economy, it may well lead to an increase in support for an escape route for the non-black, should the fourth dispensation turn out to be a black-nationalist one.

Even if there was never an ethnicity associated with a territory, its memory can be a rallying point for political leadership. In my estimation, it depends entirely on what the needs of the various parties are. Even when nobody is actively pursuing a territorial separation, the previous administrative boundaries of long vanished empires can linger like watermarks on the page, and collect political power and aspirations without the need for recognition. This places a rather heavy burden on the state which wishes to consolidate power in the shadow of former empires.

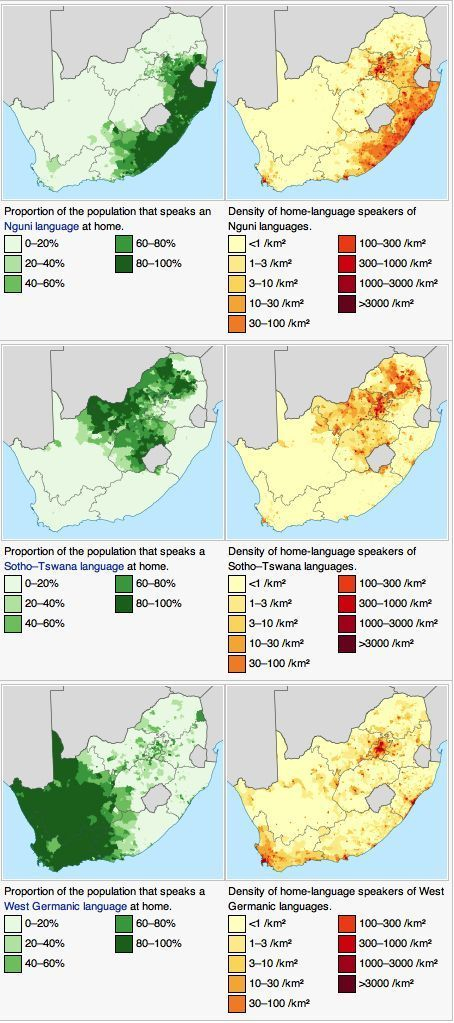

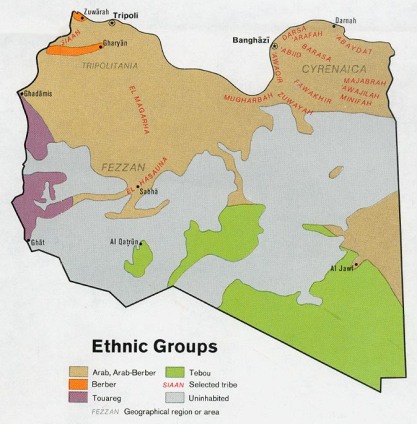

In Libya, its predecessors align, coincidentally, with the major concentrations of oil. I say coincidentally, since Cyrenaica and Tripolitania are not merely colonial provincial divisions, but the inheritance of political entities which are as old as the Roman Republic. Cyrenaica was a province of the ancient empire, and persisted as a political entity in various forms until the Allied forces united it with other Ottoman provinces (later to become Italian possessions) Fezzan and Tripolitania under the latter-Roman-Imperial moniker of Libya, ruled by the Cyrenaican Emir Idris.

Idris was perhaps rightly seen as something of a satrap for the British and French interests in the region, and Gaddafi overthrew his monarchy in a coup in 1969. His manner of governing is a rather interesting phenomenon. While he advertised a third way philosophy, his Green Book is a jumbled mess of strange declarations on every topic from climate to football. But his governing strategy was shrewd, in Machiavellian terms. He accorded a degree of local autonomy to extremely small divisions of the country, but ran almost every aspect of the state’s politics and major industries from the centre, by decree.

This method allowed community life in rural Libya to persist in a quasi autonomous way, but meant a great deal of oppression in the metropolis, and a total, vice like grip on the oil industry and other key areas like agriculture and construction, through patronage, graft and direct ownership by the ruling family and its extended clan network. By allowing popular representation at the very local level, but forbidding the formation of national level political parties, Gaddafi made sure that the centre was an absolute monolith, and when he was finally toppled by a combination of popular foment and international interference in 2011, the localised alliances re-emerged, violently.

Libya is not just divided by isolated regions with non-contiguous petroleum infrastructure and desert boundaries, but by ethnic ties which solidified under the two-tier hybrid system Gaddafi set up. This meant that when the centre failed to hold, the provinces returned. Comparing the map of the zones of control to the map of the colonial provinces of Italian Libya reveals the reason for their persistence under Italian rule – pragmatically, they were easier to govern. Under French and British occupation and United Nations mandate, the unwieldy and tyrannical homogenisation of the fictional nation of Libya was forced into existence under the domination of a hand-picked monarch.

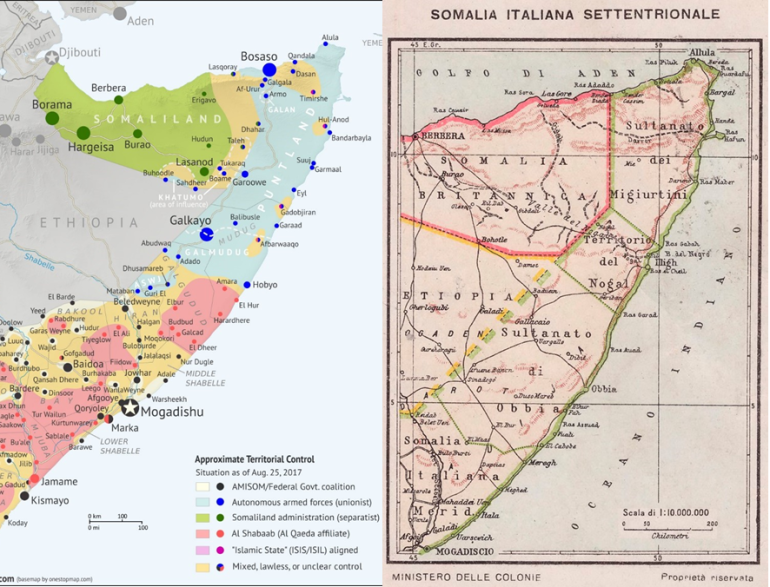

These same realities are visible in the collapse of Somalia. Much like Libya, it was seized in the early 20th century by the Italians, who united the Hobya and Majerteen sulanates with the rest of the Somali hinterlands not already occupied by the Ethiopian and British empires. The greatest peculiarity is that even after generations had passed, the divisions created by the sultans and the emperors, persisted in the unconscious memory of the people of Somalia. In 1969, Somalia was taken over by a Marxist regime. Siad Barré consolidated the new Somalia formed in the wake of the UN (read: American)-mandated independence settlement under a totalitarian and thoroughly mismanaged kleptocracy, which ground the state’s economy under a system of Marxism blended with Islamic and ethnonationalist elements.

The map of the zones of control was compiled here.

As the Ogaden war erupted, in contestation over ethnic Somali possessions within Ethiopia, the state resources were sapped almost to their absolute depletion, and after an intervening decade of bankruptcy and debt, unsustainably large IMF loans, the state fell apart in 1991, as completely as a state ever has. Even today, with all the efforts exerted by the United States and the UN, he rump government in Mogadishu holds loose control over anything beyond the city, and even there it is not uncontested. In this chaos, two states have emerged, both of which have shown themselves to be far more stable, and go utterly unrecognised.

Somaliland has emerged in the place of British Somaliland, an entity which had not existed since WWII. Puntland, emerging six years later in the place of the former Majerteen Sultanate, had not seen independent governance since the days before Italian conquest, and yet has emerged as a stable neighbour. Both of these states have shown more stability than many of their neighbours, including most recognised states in northern and central Africa. Some Somalian immigrants to London are known to send their children to Berbere to escape London’s knife crime.

That may be more a reflection on London’s decline than Somaliland’s growth, but it is a remarkable achievement nonetheless, and a damning indictment of the absurdity of the doctrine of national sovereignty adopted by the UN. While lack of recognition stokes instability, recognition of non-entities encourage struggle for central control. Rather than give the existing Somali states independence, the UN prefers to work toward putting them under the same state which massacred the Isaaq clan members of Somaliland. In a similar way, the UN is backing whoever is occupying the capital city of Libya, while the strongest army with the largest oil resources and the most regional friends is based in Tobruk. General Khalifa Haftar has managed to seize the majority of the country as of the writing of this article, while abandoning much of the desert hinterlands to local bandits. As the possibility of him seizing Tripoli loom large, talk of partition has resurfaced.

This might have something to do with the fact that among Haftar’s backers are the Russian government. The White House (which has entertained notions of partition already) and their allies in the EU may want to cut their losses and establish a stable Mediterranean sea front and prevent escalation of the migrant crisis in southern Europe. It doesn’t help much that Tripoli has struggled to maintain the fragile alliance of local actors comprising the ruling coalition. But as the above-linked article by Dr. Geoff Porter argues, Libyans still identify as Libyans. It seems to me that the idea of Libya will be just as difficult to expunge as Cyrenaica and Tripolitania, and whatever happens in the future, now that the status quo has been unsettled, and alternatives entertained, the identity of these territories will not be settled for some time to come. The war is far from over, and may yet escalate – General Hafter is clearly fighting to unite Libya under his own banner, or he wouldn’t be risking an assault on Tripoli.

But men like Gaddafi don’t come along every day. And Haftar may well not be able to foster the kind of strange unity seen under Gaddafi. He is a staunch secularist, in a country beset by powerful Islamist groups. Similarly, as stupid and cruel as the rule of Siad Barré was, his capacity to bind the nation together is not something that arrives every day. If the institutions set up by the great rulers do not last beyond their rule, the political unity created doesn’t either. And we can say much the same for our fair nation – the emergence of strange and archaic nationalisms and separatist movements has coincided with the radical repudiation of the Democratic dispensation, by young black men preferring a blend of Leninism and ethnofascism to nation-building and heritage conservation.

I think it would be fair to say that young countries with fragmented identities and distant (or perhaps not-so-distant) memories of previous (in our case, colonial) power arrangements require more long-sighted institutional arrangements than those which cater to utopian fantasies or the partisan interests of some dictator – they must outlast the short lifespan of both fantasy and real men. Equally, They should be able to fail gracefully. The Zulu kingdom and the Cape of Good Hope will both encounter extraordinary challenges in leaving, and see massive violence: they are far too integrated with the current constitution to be disentangled on a peaceable basis, at least for now. Whatever comes next in our history has to be more stable and accommodating of difference than either fascism or rainbowism, that I can say with certainty.