Economists love to disagree, but almost all of them will tell you that inflation is dead. The premise of low inflation is baked into economic policies and financial markets. It is why central banks can cut interest rates to around zero and buy up mountains of government bonds. It explains how governments have been able to go on an epic spending and borrowing binge in order to save the economy from the ravages of the pandemic—and why rich-world public debt of 125% of GDP barely raises an eyebrow. The search for yield has propelled the S&P 500 index of shares to new highs even as the number of Americans in hospital with covid-19 has surpassed 100,000. The only way to justify such a blistering-hot stockmarket is if you expect a strong but inflationless economic rebound in 2021 and beyond.

The Economist

This bizarre paragraph graced the head of the lead article of The Economist this weekend. One might wonder where they’ve been for the past 50 years.

Contents:

- Introduction

- Real Existing Mugabenomics

- Mugabenomics in one Country

- Decline…

- …and Falter

- Mugabenomics in Theory

- Muddled Monetary Theory

- Blyth

- Graeber

- Piketty

- Bregman

- Real Mugabenomics has never been Tried (TBC)

- Davos Man, Meek and Mild

- Southward Bound

- The Vainglorious Revolution

Introduction

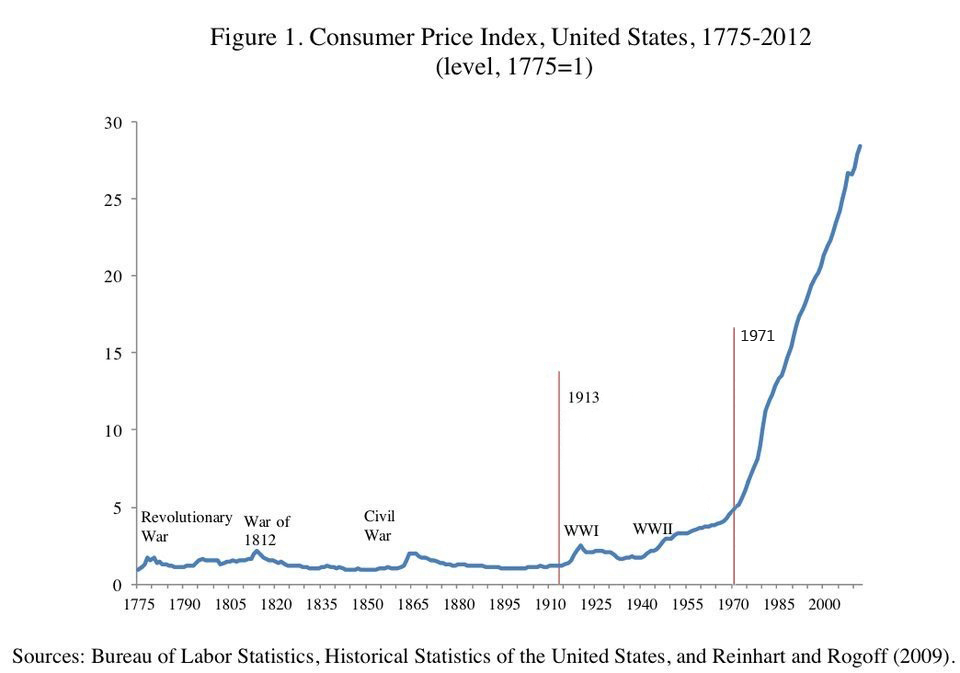

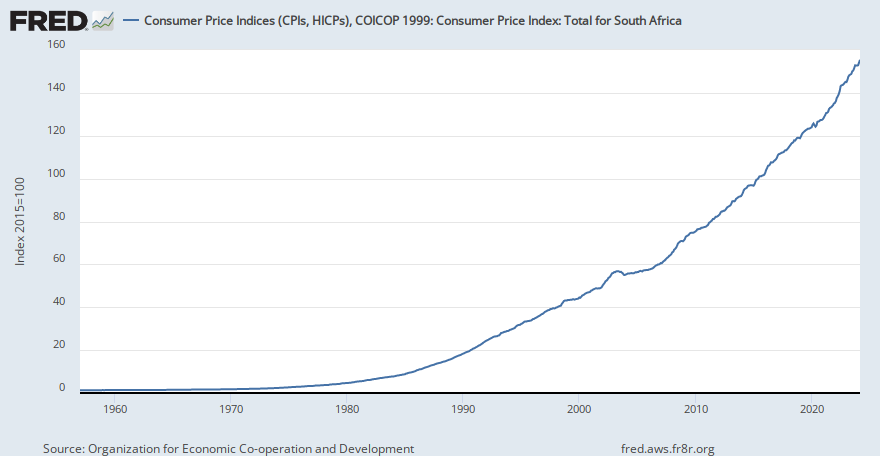

Chronic inflation is everywhere, and has been for generations already. It has come to be seen not only as acceptable, but natural and healthy. Keynesian economics has been a virtual institutional consensus for quite some time, and while its defenders might correctly point out that a contraction of the money supply is called for in times of plenty, as any schmuck can tell you, no politician will turn up a chance to feed their base. And now, his theories have been dialed up to eleven.

Modern Monetary Theory is the belle du jour. It is a simple but wildly dangerous economic theory which can be easily understood by any shaved ape like you or me. It says a government can’t run out of cash, because it can just print more. And while printing money may cause inflation, the state can always correct the excess supply of money by seizing assets and raising taxes, taking that money out of circulation. The people are reduced to less than statistics – they are not even the object of manipulation, but a meaty substrate on which the real subject of the managerial state (money) resides. While serious analysis of MMT’s assumptions about the functioning of the economy have been debunking this theory for years, feelings, as usual, are proving stronger than facts. And this is not only about free money. Increasingly, people are questioning the meaning of debt. If we can print money to cancel the banks’ debts, why not everyone else’s?

Today, money is seen by many, even intelligent and educated people, as a convenient fiction which is conjured up by wizards at the central bank, and therefore that all property and credit relations are consequently arbitrary and tyrannically imposed. It is hard to dispel this impression, especially since corrupt relationships between governments and the financial sector persist well into the post-Occupy era of wealth resentment. As I type this, the Federal Reserve Bank of America is printing over a billion dollars an hour, not a penny of which will be seen by the ordinary man until it is spent by financial corporations, and which over the next few months and years, will gradually diminish the value of his pocket change.

This use of Quantitative Easing understandably produces resentment of the “1%” (a tragically inappropriate threshold, for reasons pointed out below). This impulse provides cover for a broader collection of ideas, based on a combination of radical skepticism and wild utopian moral argument. As a result of an unrelenting encroachment of egalitarian doctrines through the Western institutions these past few generations, the morality of debt, contracts, property, personal responsibility – holding people to their word – are now considered cruel and exploitative. Holding more wealth than another is considered greedy and callous, and freedom is considered the selfish aspiration of ruthless and cold-hearted competition. Society is suffused with the Marxist moral dictum “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need”, but with the magic powers believed inherent in the fiat currency system, it now holds no limit, and the qualifications of need and ability are themselves abstracted away by the winds of technological change.

Yet curiously, this supposedly utopian egalitarian theory is also promoted by the wealthiest and most powerful members of the global elite.

The intellectual justifications for eternal inflation have reached the highest echelons of the global intellectual establishment, and has the ear of every power broker in the modern world, advertised by the elitest of the elite, the World Economic Forum. Lower down on the pyramid, Stephanie Kelton has been tugging the ears of presidential candidates, and Rutger Bregman has been pushing loonybin utopia at us for the past decade, a special combination of open borders and generous, free, unconditional handouts. His breakout book was called Utopia for Realists, although the more provocative Dutch title is more direct – translating to “free money for everyone”.

The moral-economic formula proposed, eats at the very foundations of society. When you lend money, you place your trust in people, and contribute to an intricate system of bonds, the expectation of future delivery of goods and services. On this system of trust, a vast universe of human activity is built, maintained by a faith that these bonds of trust will never be so strained as to come apart. And yet they have broken many times before, and threaten to do so again, more dramatically than ever before. Today, the intellectual and political leaders of the world do not share this faith, this devotion to honour debts and contracts. Not because they believe collapse is imminent, but precisely the opposite.

In the next installment: Real Existing Mugabenomics