For decades, a profligate political class has mortgaged almost every nation to the hilt. Like Littlefinger in Game of Thrones, they believe that credit and money printing is magic, a wonderful, chaotic ladder to paradise. This is a story about how the intellectual ecosystem of the developed world’s progressive elites acquired convergent evolution with the economic thoughts of the Zimbabwean dictator, and why there is nothing we can do until the damage is done. Those who recognise that this technocratic strategy is folly have retreated into various forms of political theology and rugged cyberpunk individualism, and attempt to formulate a picture of what is required to form a new order from the ashes they blow from the future. But in the meantime, we can debate the colour of the flames of our destruction.

Let us begin by looking at the world in miniature.

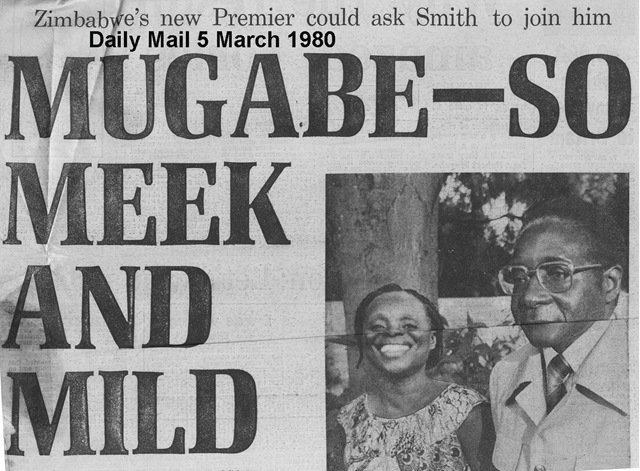

Mugabenomics in one country

The Chimurenga was a great unifying war in the eyes of the West. Pretty much everyone agreed, those recalcitrant little colonialists in Rhodesia were the devil, and only the worst people in the world had any sympathy for them. When Mugabe finally took power, articles gushing over his Jesuit education and Marxist beliefs told the world that there was no way a Catholic communist could possibly have sticky fingers. They conveniently ignored his vast and vicious pogroms on the Ndebele, and just like generations of Western journos and academics before them, the dangers of radical utopian ideas were shelved to make way for the grand narrative which has come to define the Trans-Atlantic political regime to this day – development, democracy, equality.

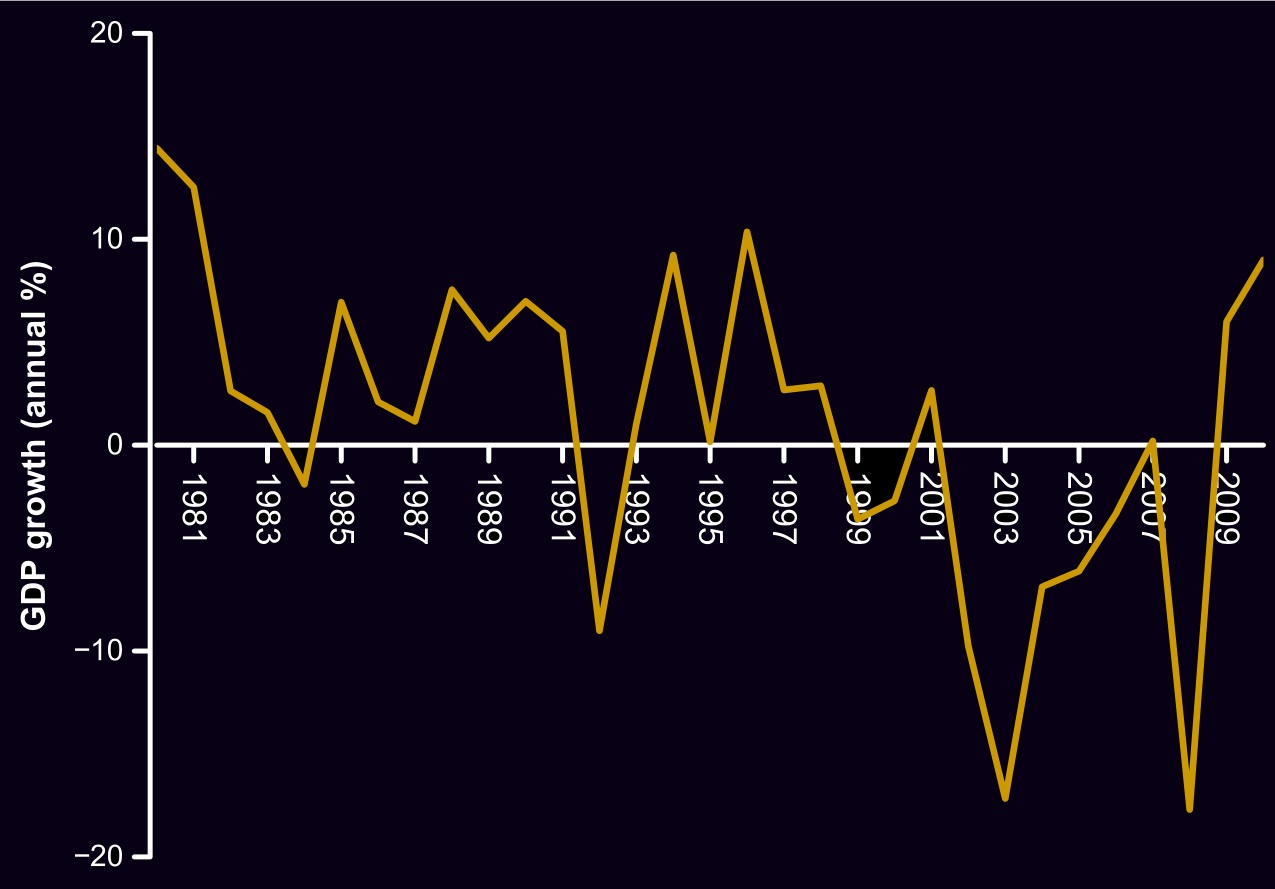

Riding off the development of a small but highly educated population, a young workforce, and a diversified mend-and-make-do economy which had sprung up to cope with sectoral shortages during the Rhodesian era of international sanctions, Zimbabwe was an exceptional opportunity for international trade. The booming local (and locally owned) economy resulted in a 14.4% growth rate in the first year of democracy, the Zim dollar was worth more than the USD, there was 10% unemployment, and foreign debt was just 11% of GDP. But this happy state of affairs gradually sunk into economic anaemia by 1990 as the economic interventions and public debt grew out of proportion to all reason.

In an effort to redistribute wealth and provide healthcare, education and welfare for his people (as well as for himself and his friends), Mugabe went on a public spending spree, instituted aggressive wage controls, and levied heavy sales and income taxes. Spending on healthcare and education tripled, and public employment ballooned. He also resettled over 70 000 families in collectivised farming programmes, falling short of his much more ambitious target of 200 000. These were a failure, and had to be bailed out of food shortage by the commercial farming sector. Nevertheless, these efforts received widespread applause from idealistic liberals and progressives. Living standards were up, and the people were healthy and educated, the envy of much of the continent.

But as the economy slowed, ZANU-PF depleted Zimbabwe’s tax revenue. With the economy near to bottoming out, Mugabe rescued it at the last minute by borrowing from the IMF and instituting structural readjustment policies in the early 90s. But these were not enough. Maintaining control over a political party composed of recalcitrant military veterans, and keeping control of a country where vicious ethnic cleansing of the Ndebele minority had taken place, required a steady stream of patronage to pacify the elite. In order to pay off the massive debt while continuing to provide for corruption and patronage, Mugabe started to print money. Within a few years, he had wiped out the economy, sending it back to pre-1950 levels, and Zimbabwe became world-renowned for hunger, poverty, violent repression and crass displays of elite wealth.

In order to provide for his military and state supporters, and to complete the racial transformation he promised, Mugabe began seizing land and handing it to loyal handlangers. After destroying the productive capacity of the agricultural sector, Zimbabwe was now in free-fall and reliant on aid for basic food security. Without property titles for collateral, the financial sector capsized. Price controls on food led to the destruction of the value chain, and store shelves emptied. But Mugabe would cling on to power in his enormous palace until he was deposed in 2019, and rapidly withered away in retirement as his family lived on in incontinent opulence. While ZANU-PF is still in charge, few support them, and vicious crackdowns on opposition and widespread vote-rigging keep a decaying kleptocratic upper crust floating above the barren landscape of a once-prosperous economy, where the American dollar has replaced the Zim.

It is worth turning to Venezuela’s recent troubles, which it closely resembles:

After years of nationalizing businesses, determining the exchange rate and setting the price of basic goods — measures that have long contributed to chronic shortages — Mr. Maduro seems to have made peace with the private sector and let it loose. And while the country’s economy continues to contract overall, the declining regulations have encouraged companies serving the wealthy or the export market to invest again […] After years of nationalizing businesses, determining the exchange rate and setting the price of basic goods — measures that have long contributed to chronic shortages — Mr. Maduro seems to have made peace with the private sector and let it loose. And while the country’s economy continues to contract overall, the declining regulations have encouraged companies serving the wealthy or the export market to invest again.

Mugabe’s cheap and promiscuous Jesuit socialism resulted in bankruptcy and brutality, and the collapse of every institution in the society, all watched over by an increasingly paranoid and corrupt dictatorship. These dictatorships have stabilised an urban elite economy in dollarised networks, but the vast majority live in penury, and access to dollars is tightly controlled. But with printing Zim$ off the table, budget deficits returned with a vengeance:

In 2017, the deficit was projected to be $400 million, yet it climbed to $1.82 billion, or 11.2% of GDP, mainly financed through Treasury bills and recourse to “overdraft” at the Reserve Bank […] It appears that the Reserve Bank is raiding the coffers of private savers. […] they had virtually no access to money in U.S. dollars from their own commercial banks. [due to the] trade deficit […] U.S. dollars are flowing out of the country faster than they are flowing in. But that can’t explain a near complete evaporation of dollars from the market economy.

The reality is that commercial banks have been forced to trade their U.S. dollars for Zim-issued Treasury bonds, with no market value, in order to cover the Reserve Bank’s overdrafts. The result is a headache in terms of everyday transactions that most of us take for granted. In order to “solve” the cash shortage problem, the Reserve bank has printed up special “Zimbabwe bonds” which are touted as promissory notes, payable in U.S. dollars at any bank. Supposedly they work like a traveler’s check, except they are issued by the government. But with no U.S. dollars generally available from banks, they have become the new money of Zimbabwe, trading on the street for about 60 cents on the U.S. dollar. After a rapid depreciation, this exchange rate has held fairly stable in recent months. If you pay for something in U.S. dollars, you get change in Zim paper bonds and coins.

[…] Even getting bond notes and coins out of the bank takes hours of queuing, which may end up with nothing on a bad day and 40 bond dollars on a good one. With physical cash “unavailable” at the teller window or ATM, instead, there is a new “virtual cash” economy that is as strange a system as I have seen in my world travels. For people working in the formal economy- accountants, retail workers, engineers and so on, everyone now uses electronic dollars, which are simply represented by numbers in a bank account. These electronic dollars are worth about half what a U.S. dollar is worth on the street, according to local observers. A physical bond dollar is worth something in between a U.S. physical dollar and an electronic dollar.

But not to worry, it can’t happen “here”, can it?.

Decline…

As Lenin keenly observed, the surest way to destroy a nation and prepare the way for revolution is to debase its currency. As falls the currency, so falls the security of all social factors, and thus social trust. A new system is demanded, sometimes even a new religion.

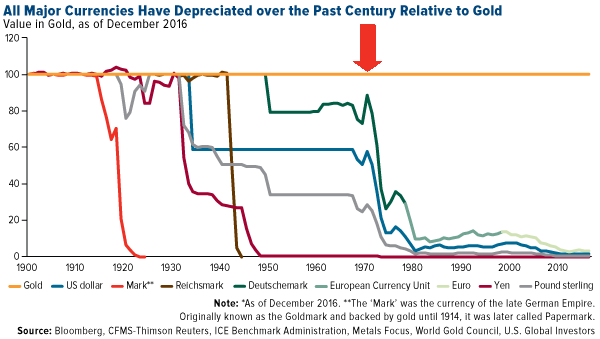

Since 1971, the consumer price index in the developed world has ballooned, accelerating a trend that began in the 1930s – the debasing of the currency. Much like in the waning years of the Roman Empire, the long wave of inflation has taken decades to play out, but it has seen little interruption. It has also dwarfed that of all previous periods of history – while individual hyperinflationary blips like Weimar Germany or Zimbabwe last but a couple of years, and destroy one country, this current trend has been spread out over a century – since the 1920s, the currency, once fully gold-backed, had been incrementally debased until it reached 8% gold backing under the Bretton Woods system, and finally went full fiat under Nixon. Goldbugs can say that metallic currency is the answer, but that clearly isn’t the issue – simple inflation is – the debasement was already occurring prior to the fiat era, and the Romans cut the silver in their coinage with baser metals to stretch the coffers.

Ultimately, this is a question of morality – as the guardian of the currency, do you not have a duty to protect the value of your citizens’ wealth?

Due in no small part to German fears surrounding the causal link between Weimar mismanagement and the advent of Hitlerism, which threatened to usher in a new age under the aegis of an eternal chthonic blood cult, the Bundesbank managed to maintain a hold on to its hard-currency philosophy just longer than the rest of the West. But they were in many ways a lone holdout. This 50-year period has seen a stratospheric increase in debt defaults and banking crises across the world, as the basis upon which states pay their debts became more tempting to manipulate, and more fluid – no longer was gold the anchor. By unpegging the dollar, Nixon took the pressure off American debt, and ensured a steady flow of cash into the financial system from the top, making it slightly easier to service American debt and keep interest rates down, by making creating money as easy as pressing “print”.

With all the abundance of the postwar period (a working class man could save for a few years and buy a house and a car), the Keynesian economists, riding off the perceived wonders of the wartime command-economy, and the boom in disposable income (which more than doubled from 1950 to 1970), argued that it was a terrible shame to allow the less well-off to continue to be so when there was so much abundance. So influential post-Keynesians like John Kenneth Galbraith persuaded President Kennedy to open up the taps and pour some extra dollars on the lower orders of American society. Johnson expanded it even further, to bribe black America into loyalty for the party that had until that generation been the bastion of slavery-apologia and segregation. As he charmingly put it, “I’ll have those niggers voting Democratic for the next 200 years”.

As Thomas Sowell pointed out, this removal of the mutual dependence of families and communities, and the introduction of individual dependence on the state tore the fabric of working class (and particularly black) society apart, leading to widespread atomisation, fatherlessness, delinquency and drug addiction, soon to be exacerbated by rising unemployment as industry was broken up and moved overseas. The easing of the need to save for periods of unemployment resulted in a loss of future orientation, and presentism became commonplace.

While the Federal reserve has created its own strange loop of structurally externalised money creation, the Europeans have engaged in a more explicitly distributist program – by redistributing Central Bank profits to countries on the basis of population, and guaranteeing the bonds of all the various states at any cost, the ECB allows the various countries to borrow money and externalise the debt, with the knowledge that interest rates will be depressed to ease the financial sector. A French, Greek or Italian PM can push for election by promising everyone early cushy retirement and public employment, but the costs of these national-level popular competitions for welfare expenditure (i.e., bribing voters) are paid by more cautious EU economies in the form of inflation. When it all goes pear-shaped, as it did in 2011, those with less political clout must take a haircut. In the meantime, the Euro depreciates.

This massive expansion in the redistribution of wealth, whether in the form of services or handouts, paid for mostly by government bonds sold to the banks, and by taxes on the middle class, has been one of the strongest features of the postwar period. But curiously, inequality has kept growing along with government welfare expenditure.

The simple reason for this is the Cantillion effect – when a dollar is printed, it reduces the value of every other dollar by a representative fraction, once it enters circulation. The first recipient of the new dollars receives the greatest benefit, because they spend first, and introduce the dollars into general circulation at pre-inflation price, which is what depresses the dollar’s value for every other market participant. And thus, the financial sector has grown like a rocket.

As more money enters the consumer cycle, rather than building assets through savings, it drives up consumer prices and incentivises the production of cheap disposable products. In the financial sector, investment is diverted from bonds to commodities and shares, into which money is dumped in the hopes to get the sorts of returns a high-interest economy would, or in the case of houses, safety. But this strained economic growth, and the financial system hit a wall, and the 70s were dominated by “stagflation” which, for much of the first world’s population, arguably never ended. This was remedied by crushing the unions, outsourcing manufacturing to the third world, and releasing the power of easy credit to allow the general population access to consumer goods. Banks stuffed the new money into assets and stocks.

While housing and precious metals might bubble and pop in waves of enthusiasm and fear, the overall trend these past 50 years has certainly been upward. Rather than considering this wasteful, the dominant mood was one of hedonism – consumption drove the economy, and was good for your self-expression, your most authentic expression of freedom, through interior décor and leisure activities. The remaining capital controls and economic protectionist policies of the developed world were smashed in 1990 as the Soviet Union fell and the entire globe settled on a new World Trade Agreement – the free market which gorged on the ashes of Western industry in the 80s now liquidated what was left and moved to greener pastures in the developing world. It was far more profitable to borrow, acquire and liquidate a company than to grow one, and so destructive acquisition proliferated, and was stored in fixed assets.

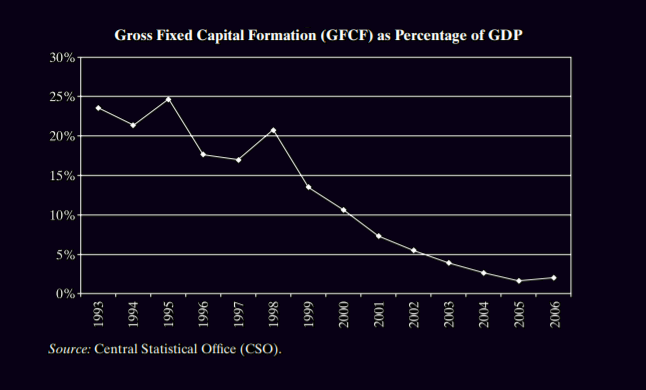

As salaries declined with globalisation and the decline of manufacturing, fixed capital formation gently slumps toward Harare. To observe the rich world’s stratospheric growth in expenditure is to witness what Zimbabwe could have been with a more educated and skilled population, and a larger reservoir of wealth to burn through – Zimbabwe’s 80’s are the West’s entire postwar history, and we are approaching saturation point.

…and Falter

Easy credit, asset concentration and chronic inflation have spread across the globe. These effects have meant a drastic change for the Western man since the days before the baby boom. Saving is fruitless compared to the expectations of the past, as the combination of inflation and service charges often outstrips interest rates, but loans are easy to get, and so the rich world racked up debt and bet it on the farm. The future doesn’t exist, only the next payment does, if you can make it.

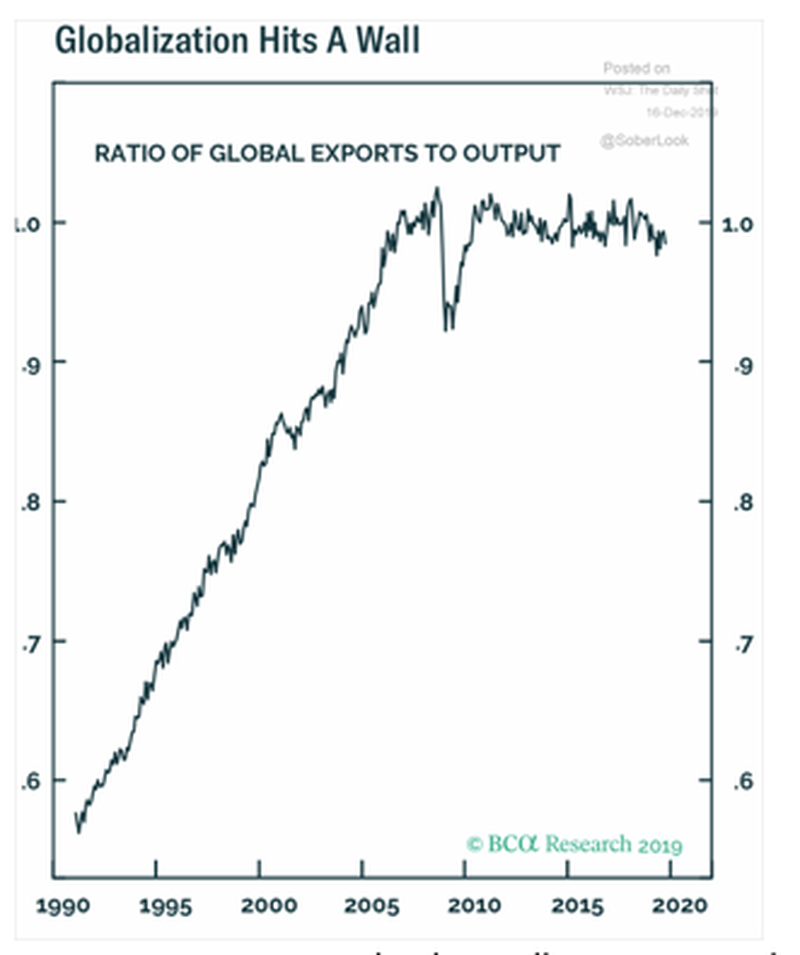

In 2007, the chickens came home to roost. Speculation on debt, and the externalisation of the risk associated with lending to profligate schmucks with no growth in wages resulted in the collapse of the sum of all promises. Ordinary people could not afford to meet the usurious borrowing schedules they had engaged, and banks had no idea what these assets looked like after they had mixed them up and sold them on. The whole lot went up in smoke. Globalisation had ended, and now there was nowhere for the finance sector to go for money. Except the printing presses.

The lessons should have been clear – debt is not good – easy credit is dangerous. But US Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson told the public that access to easy credit had to be preserved, to keep the economy and job market growing. The financial sector managed to pull the right strings, and across the world, they relied on the myth of the 1930s (stock market crash led to Hitler) to convince the politicians of the Western world to bail them out. The argument is a simple Keynesian proposition – spending “stimulates” the economy – people buy stuff, creating demand for more stuff. Idle hands are the devil’s playthings, it’s best to pay people to work to stabilise society.

However, The New Deal, based on the same principles, is widely recognised by historians to have extended the Great Depression beyond a short term shock into the long-run, grinding disaster it turned out to be. Since Keynes was alive himself, Keynesians have been mocked for paying people to dig holes and fill them back in. Jared Diamond would have something to say about this impulse and its link to the Easter Island statue-building frenzy that bankrupted their nascent civilization.

As investment opportunities dried up and stores were boarded up, the liquid capital from the mints of the West headed to the volatile yet high-yield bond markets of the developing world – Turkey, Argentina, Brazil, China, India. When the Credit Crunch finally rippled out into the world of tangible production, the system went into shock, and the debt racked up to save the banks blew a hole in the welfare system, as Greece threatened to default on their stack of pilfered handouts. Germany, France, and other strong economies strongarmed the system to avoid paying for the South’s profligacy, and funneled new consolidated Greek debt payments into their own banks, imposing a rapid reduction in wages and welfare on the southern working classes. The people were left out to dry. They soon turned to anarchism, communism, and fascism, and smashed up banks and threw rocks at policemen, impotently flinging themselves on the battlements of the state.

As the emerging markets began to contract, and desperation spread like wildfire, protests began to kick off around the world. A man in Tunisia, desperate for a chance to earn his bread and at his wits end for lack of opportunity, burnt himself to death in the public square, and sparked the Arab spring, propelling Al Jazeera into the spotlight as the Belle du Jour of the live news circuit. Seeking their own contribution, the itchy-trousered leftists of New York followed Canadian Luddite anarchist organisation Adbusters (indirectly funded by a certain NGO network) into Zuccotti Park to occupy Wall Street and demand some nebulous form of “change”, pitting the top 1% of income earners against everyone else, in a barely-disguised piece of open-air agitprop theatre.

But unlike orthodox Marxists, the Occupy movement leant on even more radical egalitarian and antinomian principles, yet lacking the spit and vinegar of the Arab revolutionaries, opted for middle-class hippy revolt where safe spaces and egalitarian epistemology reigned. It soon fizzled away, having achieved nothing of remark. But these ideas festered in frustrated pockets of academia and burnout culture – a world without the hyperwealthy, where money is free, democracy is direct, and all are hears, all are equal, no borders, no laws, no bankers, no cops.

Since the crisis, the economy has been going sideways, and nobody saves anymore, because savings are pointless – low interest rates and high banking charges make it more cost-effective to borrow money which in an increasingly uncertain labour market, results in high delinquency rates. So we invest in increasingly consolidated monopoly stocks for our pensions, who are in turn invested into government bonds, increasingly devalued by QE. The Western states are debted to the gills – levels approximating 100% of GDP have become ordinary, taken out to maintain financial liquidity and welfare expenditure, paid for by depressing interest rates and printing money.

This is the status quo. Homeownership has been made further out of reach to the average man, and savings have far less value. Chronic debt, which many Westerners in the past generation or two have piled on, is charged at a much higher interest rate than we see in the banking sector, which is the big ticket which runs the headlines. In order to save themselves from the falling returns in government bonds and the declining value of currency, international investors have increasingly turned to stock and commodity speculation, leading to asset bubbles punctuating the market at increasing volume and frequency.

But this all has its limit. In order to justify support for access to more funds for finance and welfare recipients, economists would have to make some creative arguments for the liquidation of the middle classes. Like the kings of old, the new masters of money need their own bards to sing their praises.