As news emerges that the ANCYL is attempting to revive their paramilitary training camps, following the example set by the PAC, BLF, EFF, and various other black supremacist groups, I and other South Africans must confront the possibility of a dark and bloody future. But to understand this future, we must confront a part of our dark and bloody past which seldom receives attention. In the past few years, two books with the same title and subject have been released, covering the latter days of the armed Struggle in South Africa. One, the memoirs of aging and reticent Struggle icon Charles Nqakula, and one by a scholar from the South African Institute of Race Relations, Anthea Jeffery. Their shared title, omitting the different subtitles, is “The People’s War”.

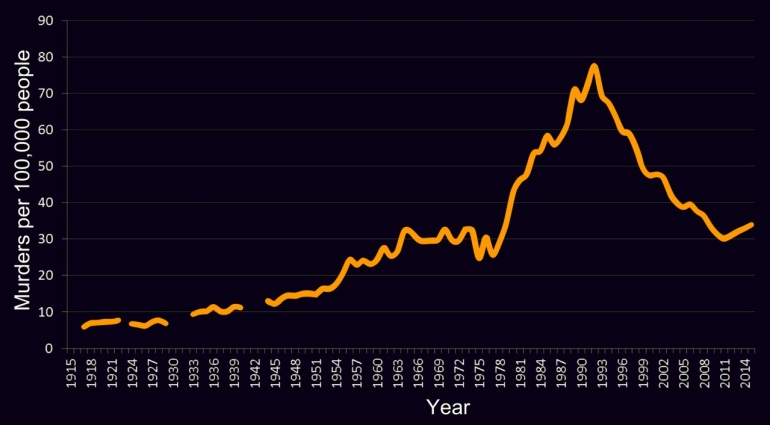

The wave of violence in the latter part of the Struggle, while officially tallied at 20 500 victims, clearly carved a much deeper wound in the national body. Without counting the spiritual and psychological repercussions of the chosen strategy, the murder rate immediately skyrocketed as the insurgency commenced in 1978, only to drop off precipitously after the incorporation of Bophuthatswana, which marked of the last violent hurdles in the democratisation project. The armed struggle in South Africa was undoubtedly necessary, but as I have written before, there is a distinct difference between “by any means necessary” and “by any means available”.

It’s hard to know, when digging up the past, whose bones belong to whom. As both apologists and critics of the ANC terror campaign will demonstrate, contemporaneous news coverage was twisted beyond recognition between the efforts of the apartheid censors, the global liberal media, and the ANC’s organised intimidation. Spies against spies, torture, chaos and omerta, partisan exculpation and self-serving lapses of memory all create a thick fog in which the prey of justice seek to hide themselves from its claws. But histories covering the other side of the Struggle, like Peter Stiff’s Warfare by Other Means, which shows the wild and cruel acts of covert terrorism carried out by the apartheid state, rely to a great extent on the accounts provided by official sources and members of the apartheid state apparatus. As it turns out, most people, even those who have committed horrific atrocities, just want to tell their story, even if it is less-than-flattering to their character. And this is true of the contributors to both Cde Nqakula and Ms Jeffery’s books.

A United Front

The political philosopher and Nazi Carl Schmitt once made a prediction, in the decade preceding the rise of the Nazis. He predicted that all future wars would be “partisan wars”. Partisans differed from traditional armies, in that there was nothing outside the conflict for them. Everyone who is not in, is the enemy. This is the world we find ourselves in in the twilight of Western civilisation. Those who wish to wipe the slate clean versus those who wish to resuscitate the body on the slab, or even puppeteer its corpse. Left vs right, in an all-out, total politicisation of every aspect of life. At that time, the novelty of revolutionary depravity was sufficient that people still considered it an historical aberration.

But it turned out not to be. 21st century Russian General Gerasimov developed the concept of “hybrid war” to describe the American global strategy of invasion. Actual invasion was but the final step, preceded by propaganda, infiltration, ideological subversion, economic and cyber warfare and false flag operations. The war was waged on multiple battlefronts, at every possible level, gradually eroding institutions until the target was primed for invasion, and even then, mystery and plausible deniability remained. Russia adopted this strategy wholeheartedly, augmented by the postmodern literary highlights of Vladislav Surkov and the multipolarist foreign-policy outlook of Yevgeny Primakov. But this is not uniquely trans-Atlantic, nor original – China has been operating on these principles in multiple realms, from the street to the ethernet highways of the trans-Pacific, for decades now, creating a vast global network of totalitarian control and influence, for the sake of “harmony”. A war of propaganda, law, protest and war, by any means available.

While the conservative Western establishment has yet to catch up with the times – from here on out, all wars are total, omnidimensional, and devoid of the possibility of neutrality – almost all wars of the past century have been centred on asymmetrical warfare and ideological subversion. As Mao put it, “everything is political” – a position taken up by Herbert Marcuse and his colleagues in the period from the 1930s to the 1960s, whose ideas now dominate the Western humanities departments. In the workshops of the woke, “silence is violence“, dissent is violence, insufficient enthusiasm is complicity. Black radicals, like their feminist co-conspirators from the first world all understand what “cancel culture” is without needing the word. It is what Orwell called “unpersoning”, and it has been a staple of the movement since they first shook hand with the red devil across the Caspian sea.

As Thami Mazwai put it in 1990, describing the latter days of the Struggle:

We have a situation in which journalists are far less exposed to arrest, detention and incarceration by the government than they used to be, but but are threatened and mishandled by political activists in the townships, in the towns, and everywhere, and are being told to “toe the line”, or else. Now when you are told to toe the line, you must make your stories convey a particular meaning, in other words you must be a propagandist. You must play the numbers game. If there were twenty people at a meeting, and it is not in the interests of the organisation that called the meeting for the public to be told that there were only twenty people present, you have got to add a couple of noughts, and if you don’t add those noughts then you become an enemy of the struggle[ …] heaven help you if you are ever cornered.

Most of the accounts of this period come from generously funded ANC mouthpieces, while Inkhata-aligned newspapers were treated as biased and irrelevant. Anyone who put the wrong broadsheet on their shop racks would have their store burnt to the ground. Those caught reading Ilanga were forced at gunpoint to eat the pages. Those buying goods from white-owned businesses were often burned to death in the streets. This sort of thinking did not originate with the contemporary Russian military, and did not originate with Nazi academics like Schmitt. It was the substance of the philosophy of war of both Lenin and Mao, and earlier revolutionary partisans, who demanded utter and total subjugation to the political goal of communism. Every element of society was to be declared for or against, and no act was immoral if it served the advance of the revolution. If a rival liberation movement arises, one does not make common cause, one subjugates or eliminates it.

Such is the philosophy of the Vietnamese generals to whom the ANC appealed for their new strategy in 1978, and such is the means by which they proceeded to exert their hegemony. A quick glance at the tactics deployed against the stupidly named new political party ATM, the wave of political assassinations deployed during the 2017 leadership contest, and the crushing of wildcat strikes in Marikana show that the ANC’s internal culture of backstabbing, violence and control still persists, albeit in a more arthritic and obese exterior.

Two People’s Wars

Both Charles Nqakula and Anthea Jeffery are telling the story of the same period of time, the same campaign, the same characters – a time of all-out radical partisanship. Charles Nqakula delivers a somewhat nostalgic book, a warm and fuzzy, sepia-toned trip down memory lane, only slightly coloured by a heart-felt, if half-hearted tone of regret, and an unspecified recrimination of himself and his comrades for not confronting sooner the corruption and culture of silence in his organisation, arguing that the rot does not start with Zuma, but in the fog of the People’s War. Here, he and Jeffery share a voice. But they separate in a disharmonious fashion when it comes to explaining why.

The clearest difference between the narratives is where they begin. Nqakula emphasises the Kabwe conference of 1985, nearly seven years into the violent campaign for total hegemony, which saw the near industrial assassination campaign against Black Consciousness, Inkhata, PAC and AZAPO members, and internal dissidents. By this point, the ANC had settled on the strategy of using a “cleansing” wave of revolutionary violence, of which Nqakula offers only restrained criticism. In fact, any criticism of any Comintern doctrine handed down from the leaders is termed “negative forces”. Members who objected to the Nguni domination of the leadership were shouted down or threatened. They were “reactionaries”.

Nqakula does not deviate in any significant way from the official narrative, and prefers to preserve his nostalgic emotions. In interviews, this is glossed over, and no difficult questions are asked. But I am not surprised that interviewers were soft on him, since at the time he was reeling from the loss of his son, and as a respected Struggle hero, he was naturally accorded a special degree of respect. Indulged in this cozy reminiscence, he makes no mention of the contents of the ANC’s grand strategy or its origins. But this omitted detail becomes the focal point of Jeffery’s entire history.

Jeffery starts her book in the dawn of the armed resistance in the 1950s, and turns her attention to the Soviet control, which saw the SACP taking control of the ANC. All central leaders, from Mbeki to Zuma, were members of the SA comintern, and issued orders in concert with Soviet doctrines, though this wasn’t simply taking orders – many were true believers, and enthusiastic Stalinists. They were almost entirely funded by Moscow throughout the 50s, 60s and 70s. But after the end of the sabotage campaign which saw the jailing of the most prominent leaders, from Mandela to Sisulu, and later the abortive attempt to trigger a guerilla war in 1967, the ANC became something of a joke to average South Africans. To them, the big movement was the IFP, who at their height in the 70s had over 300 000 members. Soviet funding slowly declined, as the situation seemed lost from the Russian perspective.

The rise of Black Consciousness which blossomed from the student movement of which Steve Biko was a significant leader, also made a dent in the ANC’s reputation. In fact, BC became the face of the resistance, and seemed at last, to present a serious challenge to the apartheid state. According to research on the departments of education, the Soweto riots and subsequent national uprising resulted in an internal loss of faith in segregated education, and consequently in the whole system of apartheid, leading to a massive loss of morale from within the racist regime. The IFP refused to play a part of the Bantustan project, which attempted to legitimate racial disenfranchisement by jettisoning black territories as “independent” republics. By refusing independence, the IFP forced the state to acknowledge the massive racial democratic deficit created by the Zulu plurality.

History is made at night…

But as this spontaneous, multi-party uprising was threatening revolution in South Africa, the ANC and Russia were out in the cold. They responded by jacking up funding to the millions of dollars, and increasing military recruitment, which kept increasing until 1989. In 1978, the Soviets organised for several ANC leaders to travel to Ho Chi Minh City, to learn from the now victorious Vietnamese how to fight an all-out guerilla war, a people’s war, against a more powerful opponent. The style and tactics adopted from the Vietnamese general Vo Nguyen Giap, termed a “People’s War“, became official policy and were outlined in the ANC’s Green Book. This is not mentioned by Nqakula, despite it being the very origin of the title of his book. A People’s war is an all out war, on every level; ideological, physical, spiritual. Any person is expendable, mere tools in conflict, and there is no middle ground. No tactic, no cruelty is too desperate or extreme.

This grand partisan effort would involve subjugating all other liberation movements to ANC control. Since the ANC were the only source of shelter for those BC activists expelled from the country during the crackdown in the late 70s, they were forced to come to the ANC for help.

“Khetani Nkabinde, a student leader from Soweto, likened the ANC to ‘sharks’ saying: ‘If you are swallowed up by them, you will never escape. They infiltrate everywhere, even the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, where you have to register when you arrive from home.’ Propaganda and political education also helped to bring the BC activists into line. The Soviets worked hard to convince the new arrivals that the ANC alone had the resources, the strategic insight, and the staying power to mount an effective challenge to Pretoria. Intimidation and coercion played a part as well. Youths who were admitted to the ANC’s camps in exile soon found that any attempt to leave was punishable by death. In addition, great pressure was brought to bear on dissidents who sought to remain loyal to BC. One of those who suffered in this way was Nokonono Delphine Kave, a close associate of Biko, who was accused (along with Biko) of being an agent of the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). She was subjected to intimidation and death threats in Zambia and then taken to the Soviet Union where she was tortured for her refusal to embrace Marxism-Leninism and endorse the ANC.”

Nqakula categorically denies the ANC having ever authorised necklacing or soft-target bombings. This is simply not true, as several quotations from its official publications, Sechaba and African Communist, attest. But they did eventually abandon the practice, not for the sake of morality, but for the optics – it was costing them international support. Demonstrating the immorality of necklacing is easy. It exceeded in cruelty any of the practices that the apartheid government implemented, and most importantly, even the ANC admitted it wasn’t necessary, which is why they abandoned it in 1987, following which the use of the method dropped off considerably.

Other neglected details include the names of any wrongdoers amongst his old comrades; he dismisses naming and shaming as being unproductive. No doubt he was remembering one of the biggest critics of internal critics of the ANC, and a true believer and frontline guerilla of the old method, Chris Hani. After being arrested for attempting to launch a guerilla war against the apartheid state in 1968, the party abandoned armed struggle to sit in opulent exile, fed by Soviet slush funds. Hani released a now infamous memo, which nearly saw him tortured to death for insisting on continuing the struggle, and for criticising their opulent lifestyle. The ANC dug new dungeons especially for his torture, and he was only given reprieve due to an intervention by Oliver Thambo. In an interview shortly before his assassination by a right wing hit squad, he seemed to reflect on this rather philosophically. But at the time it was hardly philosophical.

…character is what you are in the dark.

Despite his duplicitous omissions, Nqakula is not the bloodthirsty zealot many of his comrades were. During his education in the Soviet Union, he was drawn to the works of Gorbachev and the more humane notions of glasnost, perestroika, and liberalisation. He did not share his comrades’ adulation of Joseph Stalin. He and his wife Nosiviwe took the bold position of openly criticising the practice of necklacing, as well as attacks on soft targets.

Small kids who witnessed such a killing told, with some excitement, of how the skull of the burning victim exploded.

But in the typical fashion of the cult of loyalty, he “accepted that there was a real urgency in the war against apartheid. We also accepted that informers were the enemy and had to be dealt with as we would their masters“. Of course, he skirts around the fact that the targets were overwhelmingly not spies, but the less-connected internal critics, community members who sided with the wrong liberation party, or just unlucky bystanders. Nqakula was aware of this, but chooses to shift the blame for rumours, infighting and paranoia onto the state:

Information gathered by our structures suggested […] the suspect was sometimes innocent of all allegations. Some were considered a problem by the regime, [which] would start a whispering campaign against the victims, resulting in them being necklaced by their own comrades.

Then there is the storming of Bisho, where current president Cyril Ramaphosa and former head of communist intelligence Ronnie Kasrils knowingly led thousands of unarmed black South Africans into the machine-gun nests of the Ciskei army as the media watched, while the other leaders were in negotiation with Pretoria. No structures were touched, no perimeters breached, and 28 people lost their lives. Yet, it was declared a victory because it made for good television. This cold-blooded and flippant attitude has persisted into the modern age. In the 90s, as the population cried out about the level of violence, politicians dismissed dismissed them – Nqakula’s reaction was to tell anyone who didn’t like living in this most violent of nations to leave. Mbeki’s is just in line with is arrogant denial of AIDS, and consequently less of a surprise.

Of course for me, the worst aspect of Jeffery’s book to read was the constantly recurring images of little children, some as young as nine being murdered by the ANC. While many were splash damage from bombs and collateral from machine gun fire, others were necklaced. It takes a lot to outdo the old SA security forces for cruelty – these are people whose use of torture (including developing what is now known as waterboarding) and even human experimentation is well-documented. But, in time-honoured fashion, the crimes of the defeated receive ten times more attention than the crimes of the victorious.

The Twenty-to-Two Rule

While Nqakula’s relatively uninformative memoir was greeted with warm praise by nostalgic fellow comrades, Jeffery was lambasted as an ancien regime apologist for writing about ANC crimes. Despite the majority of the damning material coming from internal, self-inculpatory sources, just about every big-name white liberal in the Anglo papers has leapt with maximum enthusiasm into trampling Jeffery’s effort, accusing her of swallowing the apartheid narrative, because she deigned to include accounts from official sources, and failed to flatter the now-official narrative. But after having read the book, I find that the most damning evidence has come from the bloodthirsty and gleeful boasting of the enthusiastic comrades recalling their glory days of slaughter and torture. There is enough in the words of the front line soldiers to damn the movement without the corroboration of the likes of Conrad Viljoen.

...other youths “finished of wounded Inkhata warriors, one of whom had his eyes gouged out and his genitals cut off while Makhanya looked on. One injured Inkhata man was dragged down to the township and set alight, and then had rubble piled on him to prevent his escape. Wrote Makhanya [later the editor of SA’s biggest newspaper The Sunday Times], “to me he was not a human being, he was an enemy who deserved what he got. […] I enjoyed the excitement of battle: the sea of burning shacks and the sight of men running for dear life.”

The criticism is especially ironic, since the book itself seems to have preempted it. Jeffery describes the unofficial “twenty-to-two” rule, where white liberal journalists would be careful to write twenty sentences denouncing apartheid crimes before spending even two detailing the orgy of torture the revolutionaries engaged in. This reflects the truth we all know too well, that facts do not speak for themselves, and what we want to say says more about us than the truths we learn on the way.

While the whiteys bent over backwards to find perverse interpretations of the book, black academics showed even less compunction, some dismissing it out of hand without having even read it; the most obvious case of which is William Gumede, whose objections call none of the facts or sources into question, nor address any of the key arguments, sufficing his lazy self with a page and a half of personal accusation, inferring racism and apartheid apologia. His version of events, which declares that all the murders are the result of the Third Force, contradicts the personal accounts of ANC cadres on the ground in favour of the self-serving excuses of the elites. I like Gumede’s writing in general, but like a nighttime truck driver, I will not indulge him in failing to check his blind spot.

David Africa’s response likewise highlights the reluctance to accept nuance among new South Africans. For most of us today, if you were against apartheid, nothing done by opponents of apartheid is morally objectionable. Other apologists seek further imitation of Asian communism, ignoring that its success has come from relaxing economic control, not increased orthodoxy, and even at its best, comes at the price of violent and suffocating despotism. Not everyone is negative, but as usual, the defences come from the defence experts, the war nerds at defenceweb.

The Legacy

Not only the dusty realists, but also the moist brains on the radical left, like Noam Chomsky, come to the conclusion that it was not the war that defeated America in Vietnam, nor the Struggle that defeated the National Party back home in the RSA. Instead, it was the destruction of consensus and will among the enemy, who could not bring themselves to fight for control with the same bitterness and cruelty that the radicals could. The NP gave in and opened negotiations after a long international campaign which increasingly isolated the regime, and brought powerful economic sanctions. The white middle class increasingly saw the system of apartheid as morally untenable, and were open to reform, if not absolute abolition, and they voted for it, by 2-1 in a referendum. The ANC came to power after consolidating their hegemony, and spent the past the next thirty years consolidating their position as gatekeepers to the economy and the halls of power. A thousand flowers of corruption bloomed, and the old code of solidarity kept critics out of the papers and the court system.

All the while, the party leadership stalled and hesitated and prevaricated on the delivery of the economic mandate. The fall of the Soviet Union put many of them in doubt of their communist faith, and the provision of free tertiary education by an American-sponsored economic education program, as well as fear of an IMF dependency, saw a radical shift to a liberal economic model based on avoiding international debt, while abusing the new racial quota laws to seize pieces of key industries. The party is still iron-fisted and vicious regarding internal dissent, unstable and prone to factionalism and fragmentation. But significantly, they do not contest when they lose elections. That should count for something. The ANC has gone further in adapting to liberal democracy than most post-revolutionary movements.

But there are many elements of society who have passed through revolutionary institutions like ANCYL who remain extremely radical, and completely opposed to any form of law, due process or democratic opposition. These people are the EFF, PAC, BLF and many of the up-and-coming academics, who preach a combination of Stalinism and ethnofascism. Such is the thinking of every EFF fan on twitter, or indeed a good portion of black commentators on twitter in general. The understanding of revolution as total and non-negotiable has been wholly inherited from the Soviet and Vietnamese legacy, and today, those who demand delivery of what that old vanguard promised have grown back like spring brambles, and called their forebears “sellouts”.

Any voice which does not support for the totalitarian ideology offered by the rising tide of black supremacy is doomed to be marked a settler, land thief, impimpi, racist, puppet, agent, askari, coconut, non-white, or some-such dehumanising epithet. Anything against this neo-interahamwe is against all black people, and everyone they disagree with is an “agent” of “white monopoly capital”. And anything or anybody who insists white people are human, or that their interests deserve a shadow of inclusion in the moral calculus of political life, that they ought to have “rights”, are accused of siding with “white supremacy”. Necklacing is the preferred method of disposing of suspected criminals and unpopular foreigners.

The new intellectual vanguard may reject their ANC forebears, but like fingerprints on a murder weapon, they have left an imprint in the minds of the youth that has yet to fade. Nqakula was right to worry – the violence did leave a mark.