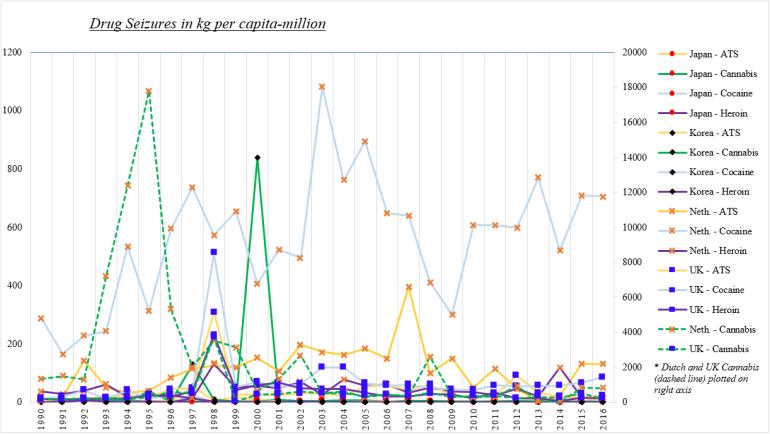

One of the most astonishing things anybody can observe comparing the countries in West and the far East, is just how much more narcotics traffic there is here. I did a brief compilation of the data on drug seizures from the World Health Organisation, and it is a pretty substantial piece of evidence in favour of a strict preventive regime.

The four countries here are the Netherlands, the UK, Korea and Japan. I had to plot Western cannabis on a separate axis, since the seizures were so massive they obliterated any distinction in other variables; they show up as dotted lines. The spike in 2000 in Korea can be attributed to a single large seizure. Other than that, the amount of drugs seized by Eastern nations is so small as to be utterly negligible, buried under the mountains of narcotics seized in the two Western nations. Despite this, what one observes browsing through Korean or Japanese coverage is a constant climate of panic at the “epidemic” they face. As a side note, it turns out that most of the weed found in South Korea comes from good old South Africa.

It is difficult to compare public attitudes, since Korea hasn’t had a national survey since 2008, nor a youth survey since 2012. Despite this patchiness, it resembles the Japanese data – less than one percent claim to have tried any drug during their lifetimes. The numbers are so low in this part of the world that solvents, like glue and paint thinner (intoxicants almost exclusively abuse by stupid teenagers and the mentally-ill homeless) are actually a significant drug category on the nation’s radar. Japan has come in for some criticism of its survey methodology. While it reports extremely low levels of drug consumption, these survey responses are not followed up, and the prefecture-level sample size is so small as to be unusable for regional analysis. This is quite frustrating, because the survey data shows very low lifetime and past-year use of any drug. The author of this critique, Dr David Brewster, appears to be somewhat on the side of liberalisation, and also appears to have been triggered by an exchange with Peter Hitchens. After having followed his blog criticism up with an academic article, his Reasearchgate profile indicates that he is in the process of researching a comparison between the UK and Japan, which I strongly look forward to. He has been helpful enough to direct me to some official Japanese sources for drug research, so I feel I must give him some acknowledgement.

Back in the West, we see regular and heavy drug consumption. A phenomenon which is rather fascinating, and a well-promoted point among liberalisation advocates, is that the harassed British drug users are using far more than the Dutch. However, the Dutch shouldn’t be celebrating. The lax attitude to enforcing drug laws has made them the centre for drug trafficking in Europe, and the vast majority of synthetic stimulants (meth, ecstasy, speed) are made in just one province of the Netherlands, the one in which I am currently staying, Noord Brabant. For those who don’t feel like picking through official sources, the Dutch version of the Daily Show did a little spot on it (English subtitles courteously included).

Portugal takes the cake for bad drug enforcement though. After Salazar’s fascist Estado Novo collapsed in 1975 to a Socialist government, the socialists decided to stop enforcing drug laws, the little geniuses. By the turn of the millennium, one percent of the population were heroin addicts. By this time, the stomach for harsh crackdowns had disappeared from the European elites, and instead, the “harm reduction” approach was adopted, seeing needle exchanges, addiction maintenance programs (giving people the drug of their choice to keep their lives on an even keel). Harm reduction, surprisingly for a national policy, actually does a reasonable portion of what its name promises. But Japanese levels of drug consumption it is not. Yet Portugal is often praised as some sort of miracle, largely based on two glowing papers which write as if the 25 years preceding the legalisation of possession did not happen.

This is a pattern that we will see repeated multiple times. After roughly a decade of serious prohibition, a Liberal or Socialist government or judicial body will disable legal enforcement and produce a long period during which drug use proliferates at a massive rate, ingraining itself deeply into the society. Lacking the political will, or perhaps suffering from some form of cognitive attachment, the government will generally provide some sort of public health policy coupled with a selective crackdown on the manufacturing, trafficking and wholesale sectors, to suppress the epidemic. To kick us off, the next article is a profile of one of the least studied countries, Korea.